UCC and its illegal shutdown of Internet in Uganda. Counting the cost of the unconstitutional actions of Uganda Communications Commission

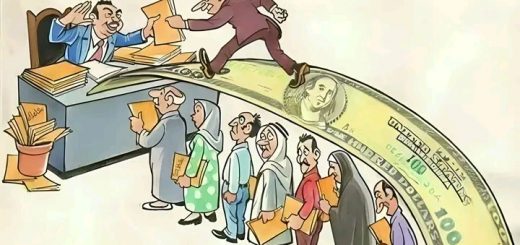

On 13th January 2021, one day prior to the presidential election, the Government of Uganda ordered telecommunication service providers to turn off access to social media. A few hours before 14th January 2021, internet access was completely turned off once the government realized that citizens were circumventing its restrictions to social media using virtual private networks. The government justified its actions on the basis of ensuring equity during the election given that Facebook and Twitter had shut down accounts linked to the NRM party and on the basis of trying to prevent the spread of disinformation, inflammatory and inciting messages and news.

Another election and another illegal shut down

On 13th January 2026, UCC again ordered the internet service providers to shut down public internet access for an unspecified period of time. The internet service providers know what UCC has ordered them to do is unlawful but none spoke up or pretended to take action to resist the government’s unlawful order. MTN Uganda and Airtel Uganda the main internet service providers did nothing to protect the consumers. The courts and the Inspectorate of Government were nowhere to be seen. Another election cycle and Ugandans must be oppressed.

The actions of the Government of Uganda outlined above violate various rights guaranteed and protected by both international legal instruments and the Constitution of Uganda. 1995 (as amended).

- The UCC violated the right to access to information.

This right is guaranteed by Article 41 of the Constitution of Uganda, 1995 as enforced by sections 2 and 5 of the Access to Information Act. It protects the right of all natural and legal persons to obtain information from state bodies except where the release of the information is likely to prejudice the security or sovereignty of the State, or interfere with the right to privacy of any other person. The right is also provided for by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The right to access to information is not limited to just being able to request information from state agencies but also extends to the means of accessing such information. For millions of Ugandans, the internet and specifically social media is their main source of information. The state has the duty not only to prevent unjustifiable interference with the rights of individuals but in certain circumstances to take measures to ensure that citizens are able to enjoy their rights. The state by turning off access to the internet prevented millions of people from accessing information in violation of the right to access to information. Article 20 (2) of the Constitution provides that the rights and freedoms of the individual and groups enshrined in the chapter shall be respected and upheld and promoted by all organs and agencies of government and all persons. The state failed on both counts. It acted as the violator of the rights that it has a duty to protect. - The UCC violated the freedom of expression of Ugandans.

The right to express one’s idea without fear of harassment and other interference is protected by Article 29 of the Constitution of Uganda. The right not only proscribes most government restrictions on the content of speech and ability to speak, but also protects the right to receive information, prohibits most government restrictions or burdens that discriminate between speakers, restricts the tort liability of individuals for certain speech, and prevents the government from requiring individuals and corporations to speak or finance certain types of speech with which they do not agree. Social media in Uganda is the way that citizens have their say on issues of public concern, express displeasure with government action and petition their representatives. Though the state can regulate harmful speech such as child pornography, it cannot out rightly prohibit speech in the guise of protecting the public. By turning off the internet, the state effectively made it impossible for millions of Ugandans to express themselves in violation of Article 29 of the Constitution of Uganda. UCC effectively banned the speech of many Ugandans by making it impossible for them to speak. - Right to property under Article 26 was violated by UCC by illegally turning off the internet.

The Constitution of Uganda under Article 26 protects the right of individuals to own property and under Article 26(2) provides that no person can be compulsorily deprived of property without prompt payment of fair and adequate compensation prior to the taking of possession or acquisition of the property. In Uganda National Roads Authority v Irumba Asumani & Peter Magelah, Supreme Court Constitutional Appeal No.2 of 2014, the Supreme Court held that the state must pay adequate compensation before compulsorily acquiring property. The state and the telecommunications companies effectively appropriated to themselves or rendered property belonging to others unless in violation of Article 26. This relates to mobile money that individuals were unable to transact with, tax and data bundles that Ugandans were unable to utilize. The state actions amounts to compulsory taking in violation of Article 26(2) and court precedent in Uganda National Roads Authority v Irumba Asumani & Peter Magelah. It can lead to an award of compensation under article 26. - UCC violated the right to due process of the law.

Due process of the law is embodied in the right to a fair hearing under article 28 of the Constitution of Uganda and the Right to just and fair treatment in administrative decisions under Article 42 of the Constitution. It is a non -derogable right under article 44 of the Constitution which prohibits arbitrary deprivation of life, liberty, or property by the government except as authorized by law. It protects individuals from arbitrary intrusion by the state in their affairs except as provided for the law. Under the Uganda commission Communications Act, Section 86, the Commission may, during a state of emergency in the interest of public safety, direct any operator to operate a network in a specified manner in order to alleviate the state of emergency. The state did not declare a state of emergency as provided for by the Constitution and therefore, it had no power to order the telecommunications companies to turn off the internet. The actions of the state were ultravires the Uganda commission Communications and therefore illegal. Given that the actions of the Uganda commission Communications were illegal the telecommunications companies had no obligation to follow them.

Constitutional rights and human rights though they are inherent and not granted by the state are not absolute and maybe limited to protect public interests or the rights of others. In Uganda, under article 43 of the Constitution, the state may impose any such limitations that are reasonable in a democratic state. Sharon and Others v Makerere University ((Constitutional Appeal No. 2 of 2004, the Supreme court held that any such limitations must serve an important state interest, be reasonable and be the least restrictive means of achieving a paramount state interest. Though the state has interest in maintaining public order and preventing inciting conduct that interest is not more paramount that protecting the rights of individuals and the means adopted of turning off the internet unduly burdened various rights protected by the Constitution including the none-derogable right to a fair hearing to which no limitations are allowed. The means adopted by the government were not the least restrictive because it could have blocked only those persons inciting violence.

Remedies available against the state and UCC

- Under section 3(2) of the Enforcement of Human Rights Act, Court proceedings to enforce human rights need not be instituted by the person whose right has been violated. They can be instituted by any one including a person acting a person acting as a member of, or in the interest of a group or a person acting in public interest. The suit should be filed in the High Court by any interested person for the benefit of all citizens. The remedies available to the citizens include, the restitution of the victim to the original situation before the violation of his or her human rights and freedoms; measures aimed at the cessation of the continuing violation of human rights and freedoms; restoring the dignity, the reputation and the rights of the victim and of persons closely connected with the victim; public apology, including acknowledgement of the facts and acceptance of responsibility; criminal and other judicial and administrative sanctions against persons liable for the violations and guarantees of non-repetition.

- It’s a criminal offense under section 11 of the Human Rights (Enforcement) Act 2019 to derogate from non-derogable rights and freedom and the prosecution may be initiated by an individual. Therefore, criminal charges can be filed against the responsible entities.

Possible defenses available to the companies and the state.

The possible defenses for the telecommunications companies include:

- Lawful orders by the state,

- Frustration

The possible defenses by the state include:

- Lawful restrictions under article 43 of the Constitution.

- Protection of public interest.

The Inspectorate of Government is the main anti corruption agency in Uganda and it had the Constitutional mandate to promote the rule of law in Uganda. If indeed the UCC violated the rights of citizens of Uganda, then it is exposed to potential liability under the Enforcement of Human Rights Act, 2019. In an ideal, world UCC would be liable to billions of shillings in damages to the citizens of Uganda for violating their rights discussed below. Consequently, public officers at UCC would by their illegal actions have led to financial loss to the state. This would constitute the corruption offense of Causing Financial Loss contrary to Section 21 of the Anti Corruption Act, 2009 as amended. As a blatant violation of the law including the Constitution, the conduct of UCC poses a serious threat to the rule of law in Uganda. As the body charged with promotion of the rule of law, the IG would be expected to get involved in investigating the actions of UCC, prosecuting the public officers involved and putting in place measures to deter and prevent such future conduct. The legal implications of the actions of Uganda Communications Commission, to wit shutting off internet access, are discussed below but we characterised the action as illegal because it was not the least restrictive means of achieving the state interest and it was implemented without following the law in place. The UCC under the UCC Act has no power to prescribe how the internet is operated except during a state of emergency. The said emergency was not in declared but even if it were declared, UCC could only impose restrictions that did not unduly restrict the rights of Ugandans: In this article we examine the due process and other implications of the shut down of the internet by the government. This article does not discuss the implications of the shut down in the context of the right to vote and the right to a free and fair election.

Read More

- Parody of Robert Kasibante v Kaguta Museveni Tibihaburwa and the Electoral Commission, Election Petition 01 of 2026.

- Ideal Amendments that should be included in the Magistrates Courts Amendment Bill 2026 of Uganda

- President Yoweri Kaguta Tibihaburwa Museveni is a minority President voted by only 7,946,772 (36.7%) out of 21,649,608 eligible Ugandan voters in the 2026 Presidential Elections

- Four years of IGG Beti Kamya drowned the Inspectorate of Government (IG) deeper into oblivion and irrelevancy but it Can be redeemed

- The Proposal to Make Magistrates Grade Ones Chief Magistrates is an efficient use of resources that will improve service delivery in Uganda