Forcing intern doctors to work without pay for the government of Uganda will be illegal and unconstitutional

Every Ugandan including you and the intern doctors have a right to work under Article 40 of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995 and the right to work under a safe working environment. See, National Security Fund v Makerere University Guest House Civil Suit No. 525 of 2015. While employed by another a person, one has a right to be paid for his or her work and the employer has a duty to ensure that there is equal payment for equal work. However, the employer may practice affirmative action and grant accommodations to employees with special needs provided that it can be done without undue hardship to the employer and other employees. See, Christopher Madrama v AG Constitutional Appeal No. 01 of 2016. (We must warn you that the result in this case that different treatment may be accorded to female public officers on account of marriage in recognition of the unique maternal functions is bad law as far as it does not recognise the duties of men and discriminates by granting preferential treatment on the basis of sex without ensuring it does not impose an undue burden on the right and without ensuring it’s the least restrictive means of achieving an important state interest).

Other obligations of the employer include providing leave to the employee, treating employees fairly, providing a fair hearing during termination for misconduct, and providing notice or payment in lieu of notice. See, Mbiika Dennis v Centenary Bank, Industrial Court, Labour Dispute Claim No. 023 of 2014 regarding leave entitlement.

If the employee has all these rights why is the state proposing to stop paying intern doctors and to extend their internship by one year to make it last two years. Though a person has a right to work and to be paid for that work, rights are not absolute. Under article 43 of the Constitution, the state is allowed to impose reasonable limitations on the exercise of our rights provided that they serve an important state interest, are narrowly tailored to achieve the state interest, do not impose an undue burden on the exercise of the right in issue and are the least restrictive means of achieving the important state interest. See, Sharon Dimache and two others v Makerere University.

Due to article 43 of the Constitution of Uganda, the state can impose licensing requires on the doctors and other professionals to ensure proper training, quality service delivery and oversight before they can be allowed to practice medicine or other professions. The government has an important interest in ensuring that doctors are properly trained so that they can provide quality services to the patients and therefore, forcing doctors to undergo internship is within the lawful authority of Parliament. The question is can Parliament decree that while under taking internship the intern doctors must work for it free of charge?

To answer this question, one must understand that to qualify as doctor one must first study for five years and attain a degree in Human Medicine from a licensed University. During these five years, student doctors work for different government owned hospitals as part of their training. Upon qualifying as a doctor, the law requires the doctor to undergo internship under the supervision of other doctors before being registered as a medical practitioner and given a license to practice medicine in Uganda. As an intern doctor you can do everything a doctor can do and you have the necessary qualifications, but you need a more experienced person to supervise and guide you. However, the reality in Uganda is that intern doctors are the ones that do the work in the hospitals and they are rarely supervised as intended.

The practice for more than three decades was to pay the intern doctors what government calls an allowance but is in fact a wage or salary under employment law. Terminology does not turn compensation for work done into something less just because you call it an allowance. If compensation is paid for work done it’s a wage or salary. It is treated as income by the tax man and accordingly taxed.

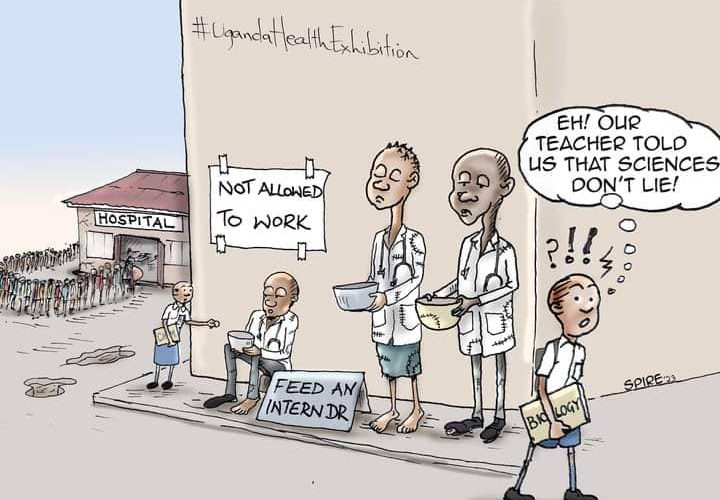

Recently, the government is considering a proposal to scrap this compensation and make intern doctors work for free in government owned hospitals. The rule has been that whether you went to a government owned university or studied at a private university, or you were a government sponsored student or a privately sponsored student you were required undertake your internship in a government hospital. While undertaking internship at the government hospital you would be paid compensation by the government. The proposed change requires intern doctors to work for the government but without compensation. It does not matter that you can get the internship at a private hospital that is willing to pay you or to which you wish to provide free services. It does not matter that you were a privately sponsored student who spent millions of your own money to study or that you were a government sponsored student who studied at the expense of the taxpayers that you to attend to during internship.

The government might have powers to force the government sponsored students whose tuition and other expenses it paid to work for free since there is a give and take between the students and the government. However, is it fair and reasonable to force privately sponsored students to work for for the government for free? To limit the right of intern doctors to be paid for their work, the limitation must comply with article 43 of the Constitution. The refusal to pay must serve an important state interest, must be narrowly tailored to achieve the state interest, must not impose an undue burden on the exercise of the right to work and must be the least restrictive means of achieving the state interest. See, Sharon Dimache and two others v Makerere University.

The state interest served by the proposal as far as I am concerned is to save money. Some short-sighted bureaucrat decided that intern doctors do not deserve to be paid for their work and thus should be forced to work for free to save money to gift to billionaire like Sudhir, Basajabalaba and the coffee deal lady and to be plundered through corruption. There is nothing wrong with saving money and it is proper that wages should be determined by the laws of supply and demand, but should we save money by forcing a person work for free. If a person is working for free on his or her volition, is he or she is being forced to do so or is that person a slave. We need to remember that article 25 of the Constitution of Uganda prohibits slavery.

The classical definition of slavery will not satisfy article 25 of the Constitution of Uganda because it is very rare to find a person who claims to own another person, but modern-day slavery exists in many countries. As recently as 2022 Parliament used the classical definition of salary in the Trafficking in persons Act. Section 2(p) of the Act which defines slavery as the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised. This definition is not helpful in describing the entire scope of slavery because modern day slavery does not always involve one person owning another.

Today slavery is less about people literally owning other people although that still exists, but more about being exploited and completely controlled by someone else, without being able to leave. One might say that intern doctors are free to leave the hospital and go home, but are they in fact free to leave the hospital and refuse to work for free. The intern doctors under the new rule must either work for the government for free or never be licensed to practice medicine. The intern doctors that studied medicine for five years at great expense so as to practice medicine have no choice but to comply if they want to be licensed.

Under Section 2(d) of the Trafficking in Persons Act exploitation” includes at a minimum … forced labor, … use of a person in illegal activities, debt bondage, slavery or practices similar to slavery or servitude … Forced labour need not be forced in the sense of applying physical force. It is entirely possible to compel a person to work for you without using physical force but by using threats and other coercive inducements. Section 2 (e) of the Trafficking in Persons Act defines forced labour as all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered him/herself voluntarily.

Forced labour, sometimes also referred to as labour trafficking, encompasses the use of force or physical threats, psychological coercion, abuse of the legal process, deception, or other coercive means to compel someone to work. Once a person’s labor is exploited by such means, the person’s prior consent to work for an employer is legally irrelevant under the Trafficking in Persons Act. The employer is a trafficker and the employee a trafficking victim. If this true the government will become a trafficker under its own laws. Maybe the government intends to amend the Trafficking in Persons Act to give itself an exception to the law.

Forced labour is prohibited under the ILO Statute and the ECtHR, case of Van Der Mussele v Belgium [1983] ECHR 13 Case No: 8919/80 (European Court of Human Rights), affirmed that forced or compulsory labour is “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. Even if the government were to amend the Trafficking in Persons Act it would still be forced labour to compel the intern doctors to work for free for the government under the threat of denying them practising licenses under international law.

The government has the lawful option of saving money by paying the intern doctors low wages. The payment of low wages alone is not evidence of exploitation. In Rooney [2019] EWCA Crim 681, the Court of Appeal emphasised that all circumstances must be considered, with low pay being a relevant factor but not in itself sufficient to amount to forced compulsory labour. The Court stated that there are circumstances of exploitation of workers which do not amount to forced labour: for example, where an employer merely pays very low wages or flouts health and safety requirements. There is also some work which by its nature can not amount to forced labour even where it is compelled: –

- Any service exacted in case of an emergency or calamity threatening the life or well-being of the community.

- Any work or service which forms part of normal civic obligations. This might include obligations to conduct free medical examinations or participate in medical emergency service.

- Any work required to be done in the ordinary course of detention imposed by a court of law or during conditional release from such detention.

- Any service of a military character or in case of a conscience objector in countries where such is recognized, service required instead of compulsory military service.

The government does not have to compel the intern doctors to work for free because low wages do not amount to exploitation or forced labour. It can let forces of supply and demand and the sanctity of contract to dictate the choice of the intern doctors. The government can save money by setting a wage it can afford and allow those that want to be paid higher salaries to be interns in other qualifying facilities. The government can benefit from the sanctity of contract and the free choice of interns to pay market value wages or lower wages and in the process keep itself in compliance with the Constitution, international obligations and its own statutes.

There are many less restrictive means of saving money that the government can use instead of forcing intern doctors to work for it for free. We have suggested a simple and effective solution that government can employ by allowing intern doctors to do their internship at other qualifying institution and accepting only those that agree to its wages. The government can also by statute require intern doctors that it sponsored to work for it for one year inconsideration for the tuition and other expenses that it covered for them. Under the analysis required to restrict enjoyment of rights under article 43 of the Constitution as set out by the Supreme Court in Sharon Dimache and two others v Makerere University, the state has available to it other less restrictive means that it can use to achieve its goals without using forced labour. Therefore, their proposed actions which violate the Trafficking in Persons Act, the right to work and the right to be paid for work done for another person are illegal and unconstitutional.

Read More

- Parody of Robert Kasibante v Kaguta Museveni Tibihaburwa and the Electoral Commission, Election Petition 01 of 2026.

- Ideal Amendments that should be included in the Magistrates Courts Amendment Bill 2026 of Uganda

- President Yoweri Kaguta Tibihaburwa Museveni is a minority President voted by only 7,946,772 (36.7%) out of 21,649,608 eligible Ugandan voters in the 2026 Presidential Elections

- Four years of IGG Beti Kamya drowned the Inspectorate of Government (IG) deeper into oblivion and irrelevancy but it Can be redeemed

- The Proposal to Make Magistrates Grade Ones Chief Magistrates is an efficient use of resources that will improve service delivery in Uganda