Discrimination in Uganda. Discrimination between public officers on contract and those that are pensionable

DISCRIMINATION BETWEEN PENSIONIONABLE AND NONE PENSIONABLE PUBLIC OFFICERS

Section 1 of the Equal Opportunities Commission Act, 2007 defines discrimination as any act, omission, policy, law, rule, practice, distinction, condition, situation, exclusion or preference which, directly or indirectly, has the effect of nullifying or impairing equal opportunities or marginalizing a section of society or resulting in unequal treatment of persons in employment or in the enjoyment of rights and freedoms on the basis of sex, race, color, ethnic origin, tribe, birth, creed, religion, health status, social or economic standing, political opinion or disability. Discrimination is prohibited by article 21 of the constitution which provides verbatim as follows:

1) All persons are equal before and under the law in all spheres of political, economic, social and cultural life and in every other respect and shall enjoy equal protection of the law.

2) Without prejudice to clause (1) of this article, a person shall not be discriminated against on the ground of sex, race, color, ethnic origin, tribe, birth, creed or religion, social or economic standing, political opinion or disability.

3) Or the purposes of this article, “discriminate” means to give different treatment to different persons attributable only or mainly to their respective descriptions by sex, race, color, ethnic origin, tribe, birth, creed or religion, social or economic standing, political opinion or disability.

This article seems to embody two freedoms, one against discrimination and another of equal protection of the law, however they are actually one right to equal protection of the law expressed differently. It creates hypothetical equality before the law for all categories of people rich poor, weak, small, large, strong etc. It stipulates that those individuals who are in similar situations should receive similar treatment and not be treated less favourably simply because of a particular ‘protected’ characteristic that they possess or due to some categorization. Non-discrimination law stipulates that those individuals who are in different situations should receive different treatment to the extent that it is needed to allow them to enjoy particular opportunities on the same basis as others .

Government action (in this case a law) discriminates if it classifies people and provides different treatment to the classifications without a rational basis. The Government action can classify individuals directly (facially) or indirectly and consequently give them different treatment. An example of a law that classifies facially (directly) is one that requires that all UNRA employees must speak Runyankole, it classifies people into runyankole speakers and none runyankole speakers whereas a law that classifies indirectly would be one that requires that all UNRA workers be five feet or less (more men than women are likely to be more than five feet). Where a law is facially neutral but creates a disparate impact in operation, to successfully challenge it an individual must show that the government intended to discriminate against the affected group.

ACCEPTABLE DISCRIMINATION

Not all classification and differential treatment is illegal or “discriminatory” because the law allows certain types of discrimination which have a rational basis. Article 21(4) of the constitution its self allows some form of discrimination. It provides that nothing in this article shall prevent Parliament from enacting laws that are necessary for—

a) implementing policies and programmes aimed at redressing social, economic, educational or other imbalance in society; or

b) making such provision as is required or authorised to be made under this Constitution; or

c) Providing for any matter acceptable and demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

In addition it has been judicially considered that parliament may treat individual differently provided that the restrictions on the right to equal protection of the law serves or protects a legitimate and fundamental state interest, is reasonable and does not unduly burden the right to equality. For example parliament may put in place affirmative action programs , may grant longer maternity leave than paternity leave, may exempt certain officers from taxation, and may tax individually different from corporate entities , among others.

DISCRIMINATION

Equality before the law does not imply actual equality but means that all individuals who are similarly placed should be treated the same way regardless of their attributes unless there is a rational basis for the difference in treatment. The requirement is that government action should be neutral whether facially or in application unless there is a good reason for the disparate treatment . Ordinarily all government action that is facially discriminatory on the basis of sex, gender, race, tribe, religion, belief or sexual orientation is unlawful and any classification on the basis of sex, race, tribe, belief or religion is presumably unconstitutional.

Therefore to succeed on a claim for discrimination you must show that:

i. An individual or class of individuals is treated unfavourably or differently (called difference in treatment) without a justification for the difference in treatment ;

ii. By comparison to how others, who are in a similar situation, have been or would be treated;

iii. And the reason for this is a particular characteristic they hold, which falls under a ‘protected ground’; and

iv. And if none facially that the government intended to discriminate against the affected group.

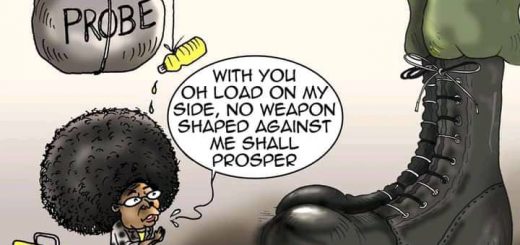

THE CASE OF IG OFFICERS.

As part of their contract of employment, officers of the Inspectorate of Government are entitled to gratuity which is paid in December of each year. However Uganda Revenue Authority charges income tax on the gratuity under the Income Tax Act. The Inspectorate of Government (IG) officers allege that they are being discriminated against because the gratuity payable to other Government employees is not similarly taxed. Section S.21 (1) of the Income Tax Act exempts pension (only) from taxation whereas section 8 of the Pensions Act exempts pension and gratuity granted under it from taxation. On the other hand section 19(1) of the Income Tax Act provides that gratuity is taxable income. The contention is that by exempting the gratuity payable under the Pensions Act from taxation, government is classifying its employees into pensionable public officers whose gratuity is tax exempt and none pensionable public officers (including private sector workers) whose gratuity is not tax exempt. The government is classifying workers into two categories and giving one category less favorable treatment and consequently denying them equal protection of the law.

In Katureebe Eridad and another v URA , the High Court considered a similar issue regarding the taxation of gratuity and terminal benefits. According to Eldad Mwangusya J, the Pensions Act only applies to pensionable public officers and therefore gratuity and terminal benefits not granted under it are taxable. In addition in the Supreme Court in Uganda Revenue Authority v Kajura SC CIVIL APPEAL N0.09 OF 2015, held that terminal benefits or golden handshakes are in other words gratuity and they are compensation from a terminated contract and are taxable under S. 19(1) (a) and (d) of the Income Tax Act (ITA). If they were exempt, the legislature would have expressly stated so under S.21 of the ITA. Neither the High Court nor the Supreme Court addressed the issue of whether the difference in treatment between pensionable officer and none pensionable officers (including public sector employees) under the Pensions Act is lawful within article 21(1) of the constitution of Uganda.

The implication of this issue not being considered in the cases is that the cases do not constitute precedents on the issue of discrimination and thus it is not necessary to overcome them in order to succeed on the issue of discrimination. Even if the cases were precedents on discrimination the Supreme Court can depart from its previous decisions and courts have usually done so . Though courts will not lightly depart from their earlier decisions, the discrimination issue was not decided in these cases and therefore there is no precedent to overcome.

STATUTORY SCHEME IN ISSUE

The following should be noted:

a) Section 19(1) (a) of the ITA lists gratuity as employment income which is taxable under section 4;

b) Section 8 of the Pensions Act exempts pension and gratuity payable under the Act from taxation;

c) Section 21((1) (n) of the ITA exempts a pension from taxation;

d) Judicial officers, police officers and military personnel are exempt from income tax;

e) Public servants under the Pensions Act are paid both gratuity and pension tax free; and

f) The formula for computing pension is as follows:

P = LS x Sal

500

Where P is Pension, LS is the length of Service in months, and Sal is the annual salary on retirement .

THE CASE FOR DISCRIMINATION

EVALUATION OF THE IG OFFICER’S CASE

The Supreme Court in Uganda Revenue Authority v Kajura did not address the issue of discrimination within article 21 and it is highly likely that had the issue been raised the court would have ruled differently. Though a court can decide a case on the basis of an argument or defense or cause of action not raised by the parties after giving them a chance to be heard, this is at the discretion of court because the court will ordinary decide on the issues as presented to it by the parties .

- Are IG officers given unfavorable treatment without good cause as compared to how others, who are in a similar situation, have been or would be treated?

In order to succeed on the basis of discrimination the IG officers must show that they were given unfavorable treatment as compared to those similarly placed. The issue in dispute being taxation of employment income, the question is whether the IG officers were given different treatment from other similarly placed employees in taxation of their income . The contention here is that whereas the gratuity payable to pensionable public officers working for the Government of Uganda is tax exempt, the gratuity payable to contractual public officers is not tax exempt. The next question to be answered is whether the pensionable officers and the officers on contract are similarly placed. To answer this we look at their circumstances such as terms of service nature of work and the government action in issue. In terms of taxation, the pensionable officers and the public officers are both taxed under section 8 of the income tax act with the same tax threshold and same rules. The difference could be in level of pay where by some public officers on contract especially in independent agencies earn significantly higher salaries than the ordinary public service, however many public servants on contract earn the same pay as their counter parts who are pensionable.

It is an essential element of discrimination that the parties involved be similarly situated or simply the person alleging to have been discriminated against must be similarly situated as those who it is argued received more favorable treatment. For example if a woman was treated more favourably than a man or a Munyankole more favourably treated than a Mutooro, (in spite of their diverse difference) if the treatment was on the basis of gender or tribe they are similarly situated if they face the same situation (payment of wages) but one of the them is treated less favourably. The situation is different if nationals were treated differently from aliens or if a child in criminal proceedings is treated differently from adults. These are considered not to be similarly situated because of their unique status though they are under the same circumstances. For example in the Moustaquim case , a Moroccan national had been convicted of several criminal offences and, as a result, was to be deported. The Moroccan national claimed that this decision to deport him amounted to discriminatory treatment. He alleged discrimination on the grounds of nationality, saying that Belgian nationals did not face deportation following conviction for criminal offences. The ECtHR held that the applicant was not in a similar situation to Belgian nationals, since a State is not permitted to expel its own nationals under the ECHR. Therefore, his deportation did not amount to discriminatory treatment. Although the ECtHR accepted that he was in a comparable situation to non-Belgian nationals who were from other EU Member States (who could not be deported because of EU law relating to freedom of movement), it was found that the difference in treatment was justified.

In the Moustaquim case (above), the complainant was not similarly situated as Belgian nationals because the rights of citizens differ from those of none citizens but was similarly situated as non-Belgian nationals who were from other EU Member States (who could not be deported because of EU law relating to freedom of movement) because they had attained citizen type rights under Belgian law. Assuming it were a Ugandan criminal case and Uganda decided to deport a Nigerian under its law, he cannot argue that he has been discriminated on the basis that Ugandan national are not subject to deportation .

Pensionable public officers and IG officers are similarly situated because their employment income (except for gratuity) is taxed similarly. We can also add that they serve the same employer but this can be a distinguishing factor from private sector employees who we shall argue are similar placed in relation to public servants entitling them to similar and equal treatment for taxation purposes.

Having established that IG officers, none pensionable public officers or and public sector officers are in similar situation as pensionable public officers, the question then becomes whether IG officers are given less favorable treatment than pensionable public officers in relation to taxation. The highest court of Uganda Supreme Court) in Uganda Revenue Authority v Kajura held that gratuity is taxable under section 19(1) (a) of the ITA, yet under Section 8 of the Pensions Act pension and gratuity payable under the act are tax exempt. In addition in Katureebe Eridad and another v URA the High court held that the pensions Act only applies to pensionable public officers. It is therefore evident that the law as interpreted by the courts treats IG officers less favourably than pensionable public service counterparts whose gratuity is not taxed. - Whether the reason for the less favorable treatment is a particular characteristic they hold, which falls under a ‘protected ground’.

Article 21 includes specific grounds for discrimination specifically prohibited by the constitution including sex, race, color, ethnic origin, tribe, birth, creed or religion, social or economic standing, political opinion or disability. Obviously IG officers are not discriminated on the basis of any of these and obviously article 21 cannot be read as giving an exhaustive list of grounds upon which a person can be discriminated. The essence of the equal protection clause in article 21 is that every person should enjoy similar rights and obligations under the law except for good cause that is consistent with the constitution . It is not tenable to argue that the prohibited grounds under article 21 are closed because you would be saying that discrimination on the basis of HIV status or discrimination on the basis of age or opinion (other than political) or sexual orientation are legal since they are not mentioned by article 21.

Protected ground means any classification or characteristic analogous to those mentioned by article 21 on the basis of which it is illegitimate to discriminate a person . The American approach on discrimination grounds is better than the European one. It focuses on the discrimination itself and considers some classifications such as race, religion and gender as suspect classifications and thus presumably unconstitutional. Other classifications are unconstitutional if they do not serve a legitimate state interest and or if they do serve a serve a legitimate state interest are overboard or unduly burden the right to equal protection of the law . For purposes of Ugandan law, article 21 envisions a situation where all discrimination based on the mentioned grounds is unlawful except if it is justified by the law. - Rational basis for the difference in treatment between IG officers and pensionable public officers

The constitutional standard in article 21 is that every person should be afforded equal protection of the law and therefore the state cannot classify its citizens and grant favorable treatment to some and unfavorable treatment to the others. However article 21 has an inbuilt exception for that kind of unequal treatment that is justifiable and it has been judicially considered that equal protection sometimes requires unequal treatment to compensate for some historical injustices or aid persons with peculiar needs or disabilities or those with a particular disadvantage . This is the justification for affirmative action programs and diversity rules in Uganda, UK and US. It trite law that individual rights are not absolute and therefore parliament may impose limitations to the exercise of constitutional rights to serve legitimate state interests such as health, national security, taxes, commerce and public welfare. However parliament cannot impose any limitation it please, it can only impose reasonable limitations that serve a legitimate state interest and do not unduly burden the citizen’s exercise of their constitutional rights . For purposes of equal protection of the law in order to justify differential treatment, it must be shown:

I. That the rule or practice in question pursues a legitimate aim; and II. That the means chosen to achieve that aim (that is, the measure which has led to the differential treatment) is proportionate to and necessary to achieve that aim. - The European Court Of Human Rights stated as follows on justification of difference in treatment:‘… a difference in the treatment of persons in relevantly similar situations … is discriminatory if it has no objective and reasonable justification; in other words, if it does not pursue a legitimate aim or if there is not a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the means employed and the aim sought to be realised’ .

- There is extensive European and American jurisprudence on discrimination which has developed the tests to be applied in justifying difference in treatment. Under European law in order to determine whether the differential treatment is proportionate, the court must be satisfied that:

- I. There is no other means of achieving that aim that imposes less of an interference with the right to equal treatment. In other words, the disadvantage suffered must be the minimum possible level of harm needed to achieve the aim sought; (American: Whether the means used is the least burdensome way of achieving the legitimate state interest and that it does not unduly burden the restricted right)

- The aim to be achieved is important enough to justify this level of interference.

- Let us assume that the exception granted to pensionable public officers is meant to compensate for low public service salaries as compared to private sector salaries or encourage talent to join public service. Arguably, the encouraging of talented people to join public service is a legitimate interest because there is a substantial public interest in good quality public service delivery. The problem is that the public service itself contains low earners who are on contract whose gratuity is taxable and very high earners whose gratuity is not taxable. This diminishes the argument that it is intended to attract talented workers. In any case there are other benefits that public officers obtain such as a pension, a chance of altruism for the public good, constitutional protection (public officers cannot be summarily dismissed), five day work week, prestige and power, which attract can talent to public service. It cannot be said that a tax exemption for gratuity serves a legitimate state interest in attracting talented workers. The state already offers substantive benefits to attract a talented work force as seen above. In any case private sector jobs in Uganda are often low paying jobs requiring longer hours than public service, without overtime pay and more than seventy percent of the university graduates unemployed. There is sufficient talent out there either in a low paying private sector job or unemployed on the streets of Kampala. For example a recent job advertisement (2016) by the Inspectorate of Government for 52 officers attracted 3,500 qualified applicants.

- In any case even if there was a legitimate government interest in attracting talent to the public service, there are other ways of achieving it without discriminating between public officers on contract and private sector employees. The government could simply put the pensionable public officers on contract like those already on contract. It could simply tax all the gratuity earnings similarly or it simply increase public service pay to attract talent instead of discriminating against certain employees. Within Wygant v.Jackson Board of Education, 476 U. S. 267, 286 (1986) the means employed by section 8 are not the least restrictive means of achieving the state interest.

- In addition the state interest in attracting talent to public service in an economy where more than fifty percent of graduates are unemployed and where there are massive benefits already granted to public officers is not important enough to deprive Ugandans of equal protection of the law . It cannot be argued that the exception granted to pensionable public employees allows for collection of government revenue yet it implodes it.

- Given the constitutional prohibition in article 21(1) against discrimination and the guarantee of equality before the law, it is discriminatory for contractual gratuities payable to public officers and gratuity payable to private sector workers to be subject to taxation yet gratuities payable to pensionable public officers are not subject to taxation. This difference in treatment serves no legitimate government interest and therefore violates the rights of none pensionable public officers and public sector workers. However it should be noted that the tax exception provided to the emoluments of judicial officers’ services, police officers and military officers is lawful since it serves a legitimate state interest in judicial independence and national security respectively. On the other hand the difference in treatment in issue here has no rational basis and therefore is discriminatory and unlawful.

- Whereas the jurisdiction to interpret the constitution is vested in the Constitutional Court under article 137(3) of the constitution, the jurisdiction to enforce constitutional protections is vested in the High Court of Uganda under article 50 of the constitution . In addition the High Court has the power under article 273 to reconcile existing laws to comply with the constitution. The Pensions Act having been in existence prior to the 1995 constitution is subject to the High Court jurisdiction under article 273. The High Court has unlimited original jurisdiction and therefore it can inquire into whether section 8 of the Pensions Act discriminates against none pensionable public officers and private sector employees in taxing their gratuity while exempting the gratuity of pensionable public officers. Having found that section 8 is discriminatory under the general principles of law, the High Court can reconcile section 8 of the Pensions Act with article 21(1) by interpreting it (section 8 of the Pensions Act) to comply with article 21(1) under article 273. What the High Court cannot do is venture into the interpretation of article 21 but it is within its powers to inquire into whether section 8 is discriminatory by hearing the parties evidence and argument for and against discrimination.

- Consequently it was not really necessary to petition the Constitutional Court to interpret article 21 of the constitution because it was within the competence of the High Court to determine whether section 8 of the Pensions act is discriminatory and reconcile it with article 21 if it found that it is discriminatory. The case of the IG officer’s is for enforcement of the constitutional guarantee of equal protection of the law and it could have been accomplished by a High Court suit. Even if issues of interpretation arose, the High Court could have made a reference to the Constitutional Court under article 137(3) .

- In Mbabali Jude V Edward Kiwanuka Sekandi (2012) , Justice Remmy Kasule JA/JCC, explained the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court.

- “…the Constitutional Court adjudicates matters requiring interpretation of the Constitution, and not necessarily, enforcement of the Constitution, except where upon determination of the issue of interpretation of the Constitution, the said court considers, on its own, that there is need to grant additional redress. In such a case, the Constitutional Court may grant other redress in addition to having interpreted the constitution or it may refer the matter to the High Court to investigate and determine the appropriate redress: See: Article 137(4) (a) and (b) of the Constitution”

- The statement by Remmy Kasule JA/JCC, above, suggests that even if the Constitutional Court were to interpret article 21, it could refer the case back to the High Court for determination. In our context however though our constitutional petition could be sustainable, given the delays associated with the Constitutional Court, the best avenue was to seek enforcement in the High Court and seek its exercise of its jurisdiction under article 273.